Benvenuto Cellini was a Florentine sculptor living in 1500’s Italy. He is famous for a statue of Perseus commissioned by Cosimo d’Medici that he worked on for 9 years. Not only did he leave behind beautiful sculptures and works of metal and jewels, Cellini wrote an autobiography detailing the memories of his experiences. You can read the book for free online: http://ebooks.adelaide.edu.au/c/cellini/benvenuto/autobiography/index.htm.

Statue of Perseus, Piazza della Signoria, Florence – Canon S45 Holding medusa head. (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

His story begins, as it should, in his youth. At one point he describes a scene in which his father, playing an instrument and singing, notices a tiny lizard at the center of the fire burning in the hearth. He calls his children, Cellini and his sister, to see the marvelous creature. His father tells them that no person has ever been credible enough to prove it’s existence. Whether or not Cellini actually witnessed a Salamander, as the tiny flame lizard was called, if it was just a trick of fire and glowing coals or a made-up fantasy to enliven his autobiography, this particular anecdote shows that Cellini, even in youth, had a taste for the mysterious and occult- which I believe greatly influenced his art.

Growing into manhood, Cellini makes friends with Roman dignitaries, including Pope Clement. While in Rome, he meets with a curious priest who knows a good deal of arcane languages and reveals his knowledge on the art of necromancy and evocation. Cellini, desiring all his life to see an operation of necromancy, conspires with the priest to perform a ceremony at the Colosseum in Rome. Here I will leave you with an excerpt from his autobiography that details his encounter with the spirits.

“IT happened through a variety of singular accidents that I became intimate with a Sicilian priest, who was a man of very elevated genius and well instructed in both Latin and Greek letters. In the course of conversation one day we were led to talk about the art of necromancy; apropos of which I said: “Throughout my whole life I have had the most intense desire to see or learn something of this art.” Thereto the priest replied: “A stout soul and a steadfast must the man have who sets himself to such an enterprise.” I answered that of strength and steadfastness of soul I should have enough and to spare, provided I found the opportunity. Then the priest said: “If you have the heart to dare it, I will amply satisfy your curiosity.” Accordingly we agreed upon attempting the adventure.

The priest one evening made his preparations, and bade me find a comrade, or not more than two. I invited Vincenzio Romoli, a very dear friend of mine, and the priest took with him a native of Pistoja, who also cultivated the black art. We went together to the Coliseum; and there the priest, having arrayed himself in necromancer’s robes, began to describe circles on the earth with the finest ceremonies that can be imagined. I must say that he had made us bring precious perfumes and fire, and also drugs of fetid odour. When the preliminaries were completed, he made the entrance into the circle; and taking us by the hand, introduced us one by one inside it. Then he assigned our several functions; to the necromancer, his comrade, he gave the pentacle to hold; the other two of us had to look after the fire and the perfumes; and then he began his incantations. This lasted more than an hour and a half; when several legions appeared, and the Coliseum was all full of devils. I was occupied with the precious perfumes, and when the priest perceived in what numbers they were present, he turned to me and said: “Benvenuto, ask them something.” I called on them to reunite me with my Sicilian Angelica. That night we obtained no answer; but I enjoyed the greatest satisfaction of my curiosity in such matters. The necromancer said that we should have to go a second time, and that I should obtain the full accomplishment of my request; but he wished me to bring with me a little boy of pure virginity.

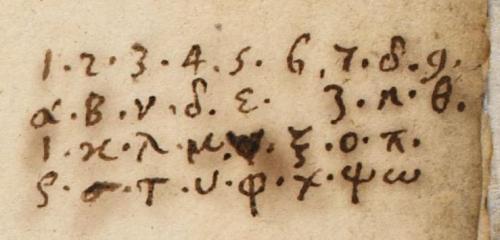

I chose one of my shop-lads, who was about twelve years old, and invited Vincenzio Romoli again; and we also took a certain Agnolino Gaddi, who was a very intimate friend of both. When we came once more to the place appointed, the necromancer made just the same preparations, attended by the same and even more impressive details. Then he introduced us into the circle, which he had reconstructed with art more admirable and yet more wondrous ceremonies. Afterwards he appointed my friend Vincenzio to the ordering of the perfumes and the fire, and with him Agnolino Gaddi. He next placed in my hand the pentacle, which he bid me turn toward the points he indicated, and under the pentacle I held the little boy, my workman. Now the necromancer began to utter those awful invocations, calling by name on multitudes of demons who are captains of their legions, and these he summoned by the virtue and potency of God, the Uncreated, Living, and Eternal, in phrases of the Hebrew, and also of the Greek and Latin tongues; insomuch that in a short space of time the whole Coliseum was full of a hundredfold as many as had appeared upon the first occasion. Vincenzio Romoli, together with Agnolino, tended the fire and heaped on quantities of precious perfumes. At the advice of the necromancer, I again demanded to be reunited with Angelica. The sorcerer turned to me and said: “Hear you what they have replied; that in the space of one month you will be where she is?” Then once more he prayed me to stand firm by him, because the legions were a thousandfold more than he had summoned, and were the most dangerous of all the denizens of hell; and now that they had settled what I asked, it behoved us to be civil to them and dismiss them gently. On the other side, the boy, who was beneath the pentacle, shrieked out in terror that a million of the fiercest men were swarming round and threatening us. He said, moreover, that four huge giants had appeared, who were striving to force their way inside the circle. Meanwhile the necromancer, trembling with fear, kept doing his best with mild and soft persuasions to dismiss them. Vincenzio Romoli, who quaked like an aspen leaf, looked after the perfumes. Though I was quite as frightened as the rest of them, I tried to show it less, and inspired them all with marvellous courage; but the truth is that I had given myself up for dead when I saw the terror of the necromancer. The boy had stuck his head between his knees, exclaiming: “This is how I will meet death, for we are certainly dead men.” Again I said to him: “These creatures are all inferior to us, and what you see is only smoke and shadow; so then raise your eyes.” When he had raised them he cried out: “The whole Coliseum is in flames, and the fire is advancing on us;” then covering his face with his hands, he groaned again that he was dead, and that he could not endure the sight longer. The necromancer appealed for my support, entreating me to stand firm by him, and to have assafetida flung upon the coals; so I turned to Vincenzio Romoli, and told him to make the fumigation at once. While uttering these words I looked at Agnolino Gaddi, whose eyes were starting from their sockets in his terror, and who was more than half dead, and said to him: “Agnolo, in time and place like this we must not yield to fright, but do the utmost to bestir ourselves; therefore, up at once, and fling a handful of that assafetida upon the fire.” Agnolo, at the moment when he moved to do this, let fly such a volley from his breech, that it was far more effectual than the assafetida. 1 The boy, roused by that great stench and noise, lifted his face little, and hearing me laugh, he plucked up courage, and said the devils were taking to flight tempestuously. So we abode thus until the matinbells began to sound. Then the boy told us again that but few remained, and those were at a distance. When the necromancer had concluded his ceremonies, he put off his wizard’s robe, and packed up a great bundle of books which he had brought with him; then, all together, we issued with him from the circle, huddling as close as we could to one another, especially the boy, who had got into the middle, and taken the necromancer by his gown and me by the cloak. All the while that we were going toward our houses in the Banchi, he kept saying that two of the devils he had seen in the Coliseum were gamboling in front of us, skipping now along the roofs and now upon the ground. The necromancer assured me that, often as he had entered magic circles, he had never met with such a serious affair as this. He also tried to persuade me to assist him in consecrating a book, by means of which we should extract immeasurable wealth, since we could call up fiends to show us where treasures were, whereof the earth is full; and after this wise we should become the richest of mankind: love affairs like mine were nothing but vanities and follies without consequence. I replied that if I were a Latin scholar I should be very willing to do what he suggested. He continued to persuade me by arguing that Latin scholarship was of no importance, and that, if he wanted, he could have found plenty of good Latinists; but that he had never met with a man of soul so firm as mine, and that I ought to follow his counsel. Engaged in this conversation, we reached our homes, and each one of us dreamed all that night of devils.”

In his next chapter, Cellini goes on to describe the necromancer-priest’s efforts to persuade Cellini to visit an occult master in Norica, a place infamous for witches, herbalists, and poisoners. While Cellini desires to consecrate a book of magic with the priest, especially to dissuade the demons from doing harm to him, he refuses to do so until he finishes his work. He then admits that he eventually forgot all about the demons, his Angelica, the priest, and the book.

Circle of the Art from The Treatise of Solomon, the Greek Forebearer of the Italian Key of Solomon

Now, Cellini either actually encountered these demons in the Colosseum or he was fortunate enough to come across a book of magic and, with a good imagination, wrote a story of how he though such an operation would go. Either way, when I came across this story I was just beginning to study the Solomonic Arts, beginning with one of the oldest manuscripts available The Treatise of Solomon. I was surprised to see that Cellini describes the operation, and it’s effects, very similarly to how the Treatise details the ritual.

For example, the Treatise instructs the magician to perform the ceremony in several auspicious places, one of which being “at a place where someone was killed in old times.” The Colosseum fits this perfectly. The necromancer dons his robes, traces circles in the ground, chants his invocations, all the while incense burns. The demons appear and the priest tells Cellini to ask them what he wants, which is a lover, Angelica. Interestingly enough, the operation in the Treatise comes with two conjurations that follow the Circle ceremony, one for Love and one for Money.

The following night they assemble once again in the Colosseum. This time the priest requested Cellini to bring a young, virgin boy with him. Virgins are not peculiar in the Solomonic Art, they attend these ceremonies to be mediums and seers, not sacrifices. The young boy tells the priest and Cellini that he sees multitudes of demons, flames approaching them from every side, and four giant demons. This also parallels the operation in the Treatise and other grimiores, as there are usually four great demon kings that rule from one of the cardinal directions. In the Treatise they are named Loutzipher from the East, Asmodai in the North, Astaroth in the West, and Beelzebub in the South.

When the group wishes to banish these demons using the time-tested method of burning Asafoetida, which is quite palatable but reeks of sulphur, Agnolo cannot break away from his fear to put the herb on the fire. When Cellini shouts at him that this is no time to be afraid, he lets out a great blast from his bottom. Some translators of Cellini’s Autobiography will carefully describe this scene, as not to offend the more sensible types. Other translators will tell it how it is, that Agnolo shit his pants. This was enough to make the virgin boy begin to laugh and report that the demons were fleeing the Colosseum.

I love this story because it is a rare example of someone’s honest (if not false) experience with the Solomonic arts in the Renaissance. It has also given me a glimpse into what may happen, or is expected to happen, when I have finally assembled my Solomonic implements and regalia to trace the circle and venture into it. Though, my endevors will not be seeking Love or Money though demonic forces, but rather take upon myself what Solomon sought to do in the ancient Testament of Solomon. I shall converse with the spirits and ask “Who are you and what do you do?” I believe there is more to the relationships between Magician and Spirit than the mere words of the grimoires reveal.